How Music Royalties Work (An Easy Guide)

Collecting royalties is an important part of an musicians income. Whether you’re a composer, a music producer, or a DJ, you should collect royalties to ensure that you’re getting your fair share whenever a song is streamed, sold, or used in a TV commercial.

Some creators tend to avoid music royalties because they find them to be too bureaucratic. However, collecting royalties is simpler than it seems. I will try to guide you through the entire process in this article.

Disclaimer: We are not lawyers, and the following information refers to how music royalties generally work in the United States. Royalty collection is different from country to country, so please keep in mind that some information may not apply if you live outside the U.S. Always check with a lawyer in your area if in doubt!

Contents

Copyright laws: The Basis of Music Royalties

Music royalties exist because of copyright laws. Copyright laws in the United States are a constitutional right meant to protect and incentivize creators. It applies not only to authors (such as musicians, writers, painters, etc.) but also to inventors.

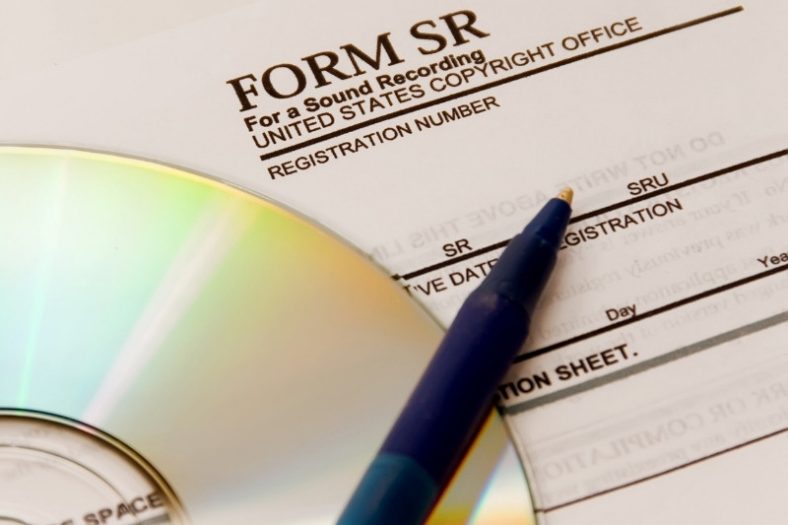

Thanks to copyright laws, authors own a monopoly over their creations. This means that if you make a song in your bedroom, for instance, you are automatically entitled to it. However, there are two things creators need to do before being legally able to collect royalties:

- Record their creations in a tangible medium. This means that one’s not entitled to a work of art simply because he or she imagined such a work of art. Examples of tangible mediums include, for instance, a sound recording.

- Register their creations with a performance rights organization (PRO). For a creator to become the legal author of a work of art, he or she must first register such work of art with a performance rights organization. You can learn all you need to know about PROs in this article.

When an author owns a work of art in the United States, he or she is given five fundamental rights over such a work of art:

The right to derive

Meaning that only the author should authorize the creation of a work of art that derives from his or her work of art. When a book is adapted into a movie, for instance, the movie producers first need to obtain the writer’s authorization.

The right to distribute

Meaning that the author is given control over how a work of art should be transferred to others. Thanks to this right, an author can, for instance, prevent an unreleased work of art from being sold.

The right to reproduce

Meaning that the author can reproduce his or her work of art via any medium he or she finds the most desirable.

The right to display

Meaning that the author has control over how and when a work of art should be displayed; it’s similar to the right to performance, except it doesn’t apply to music but rather painting and sculpture.

The right to perform

Meaning that the author is entitled to a sum whenever a work of art is publicly performed. This right isn’t limited to live performances, but also includes instances when, for example, a song is used in the soundtrack of a movie.

How to collect music royalties

To collect music royalties, an author must first register his or her work of art with a performance rights organization. Performance rights organizations act as the intermediary between artists and the organizations that use their songs (such as radio, music venues, or streaming services).

Before collecting music royalties, there are a few things you should know: how to signup with a performances right organization (1), what type of work is rewarded with music royalties (2), how royalties get split between creators (3), and what’s the role of publishers in all of this process (4).

1. How to signup with a PRO

Signing up with a performance rights organization is one of the best ways for musicians to make a living online. Nowadays, all you need to do to start earning royalties is to visit the website of your local PRO and create an account.

If you live in the United States, BMI and ASCAP are the two most popular options. You may have to pay to sign up with a major PRO, but believe me: if you’re creating songs, producing other artists, or performing with established musicians, it’s worth it in the long run.

2. What kind of work is rewarded with music royalties

You can’t own a copyright share in a song just because you’re showing it to all of your friends on social media. Other than that, though, virtually all kinds of work can be rewarded with music royalties. Royalty-eligible work falls under three major categories: composition, master, and performance.

- Composition: refers to the author(s) who created the song. This is a broad category that includes everyone from the composer who made the song’s chords and melody to the lyricist. If you’re making a tune and have a friend in the room giving you feedback, your friend can also be entitled to a composition fee.

- Master: refers to the tangible medium in which the song was created. Once a song is composed, it must be recorded to a tangible medium such as a CD, a vinyl record, or even an MP3 file. Either way, the tangible medium corresponds to the master. This means that if you compose a tune and self-release it through Bandcamp, you are rewarded with both the composition and the master music royalties.

- Performance: refers to the work of the people who performed in the song. Performance royalties can add up to the composition and master royalties. If you’re a self-published singer-songwriter who makes music completely alone, then you should be entitled to the composition, master, and performance music royalties. However, you should be entitled to performance royalties even when you sing a few lines in a friend’s song or play a bass solo in someone else’s composition.

Please keep in mind that, while legally valid, these three music-royalty categories are not explicitly differentiated per the U.S. copyright law. Outside the United States, some PROs attribute different guidelines and royalty fees to each one of these categories.

3. How royalties get split between creators

Splitting royalties is up to the creators involved in a work of art, and it’s done according to a pre-established percentage. This percentage may vary from PRO to PRO. In the United States, BMI and ASCAP (the country’s two most popular PROs) use, respectively, a 200% and a 100% scale. What does this mean?

Imagine you register a work of art with BMI. Since BMI uses a 200% scale for their music royalties, this means that the composer(s) is entitled to up to 100% of authorship rights and that the publisher is entitled to up to 100% of publishing rights. The maximum percentages given to the author and the publisher are always the same (in the case of ASCAP’s 100% scale, it’s divided equally by 50%).

If you’re a lonesome music producer who has just released a beat on SoundCloud, then you’re entitled to 100% of the beat’s authorship rights (because you made the beat alone) and 100% of the beat’s publishing rights (because you don’t have a record label and you published the beat on the Internet yourself). But what happens when other people get involved?

When two or more people work in the creation of a work of art, it’s up to them and only them to establish a fair division of the corresponding royalty rights. There are no rigid, legal guidelines on how to conduct this process. However, most creators agree that splitting royalty should be done fairly.

It’s fair that each of you gets 50% of the song’s royalties if you and a friend spend weeks in the studio making a new pop song. Let’s say you’ve spent weeks working on a pop song, and a friend shows up at the last minute to add a few basic arrangements. In this case, it’s fair that you should get a higher percentage than your friend.

To put it simply, music royalties get split through a gentleman’s deal. It’s an unofficial contract made between creators. To avoid stress and make sure you’re treating your collaborators right, you should always attempt to make the fairest possible division.

4. The role of publishers

The copyright law wasn’t invented yesterday. While self-published musicians make the norm in today’s world, recording music was once almost impossible without the help of a label. The existence of specific publishing royalties ensures that both the creator and the label can be fairly rewarded.

This is why PROs divide royalties between authors and publishers equally. This way, the author never loses his fair share of ownership, and the publishers continue to have a motivation to invest in authors.

Please keep in mind that, in case you’re a self-published musician, you must register your work both as an author and a publisher. If you’re an unsigned artist uploading songs on the Internet or paying for the release of your CDs, then you qualify automatically as a publisher.

Types of royalties

Music royalties aren’t all made the same. There are four distinctive types of royalties:

Mechanical royalties

Every time a copy of a work of art is made, royalty is owed. This means that if a song is featured in a compilation album, for instance, the composer of such a song is entitled to its mechanical rights.

Performing royalties

Every time a work of art is publicly performed, royalty is owed. If your song is used in a DJ set, you’re entitled to a fee. If your song is being covered by an artist in a live performance, you’re also entitled to a fee. Performing royalties aren’t limited to live performances, though: they also include instances in which a song is played on the radio or used in a theater show, for example.

Synchronization royalties

Every time a work of art is used in a video or other multimedia format, royalty is owed. For many creators, synchronization music royalties are the ultimate golden goose: when a song is used in a movie.

For example, its composer is not only entitled to its synchronization royalties (referring to the song’s actual usage) but also to its performing royalties (referring to every instance the song’s performed as part of the movie, i.e., every time the movie is publicly reproduced). If a soundtrack album of the movie is released, the song’s creator is additionally entitled to mechanical royalties.

Print royalties

Every time a derivation of a work of art is printed, royalty is owed. Print royalties were created mainly because of sheet music. When the tab to a song was included in a commercially-available sheet-music book, the song’s author was entitled to a certain royalty.

Nowadays, print royalties apply to all forms of music-derived monetization. If a popular brand uses one of your lyrics in their new collection of t-shirts, for example, then you’re entitled to a certain fee.

Music royalty fees

Music royalty fees may vary over time, and there are still some obscure aspects to it. The money flows from sources such as radio stations, TV networks, concert venues, or online streaming platforms to a performance rights organization. It’s then up to the PRO to distribute the money between the authors and publishers, always per the authorship and publishing right’s percentage.

The below table includes some rough figures, of course, the actual royalties can vary massively in the industry. For reference sources and additional information, please check the following great videos: Royalty Exchange’s video on the general principles of music royalties and Robert Teegarden’s video on royalty accounting.

| Service | Fee |

| When a song is sold | $0.091 |

| When a song is streamed by a subscribed listener | $0.0022 |

| When a song is streamed by an unsubscribed listener | $0.0017 |

| When a song is used in a TV show | $30K – $60K |

| When a song is used in an ad | $250K – $400K |

| When a song is used in a video game | $5K – $20K |

| When a song is used in a movie | $50K – $100K (or even more) |

Frequently asked questions

How are music royalties calculated?

Music royalties get calculated according to use and percentage. Every time a work of art is used (streamed online or played on the radio, for instance), its author(s) is entitled to a certain amount of money. The author(s) is then rewarded according to its ownership percentage.

Are royalties paid every time a song is played?

Music royalties are paid every time a song is played. If a song is getting publicly used in any way or form, then its author(s) are entitled to a certain fee. This includes everything from online streaming and film soundtracks to having a song’s lyrics featured in a book of poems.

How long do music royalties last?

In the United States, authors are entitled to music royalties their entire life, and up to 70 years after passing away. The exact number may vary from country to country. Once music royalties expire, works of art become public domain, meaning they can be freely used by all.

That’s why everyone can use a composition by Beethoven or Bach in a record without paying any royalties. Considering these classical composers passed away hundreds of years ago, it wouldn’t make any sense to still pay music royalties to their heirs or publishers.

However, a public-domain composition shouldn’t be confused with a copyrighted master or performance. Glenn Gould’s Beethoven sonatas, for instance, are not public domain because even though they use compositions by Beethoven, they’re a work of art in itself that was initially released in the ’50s.

How much does a song make in royalties?

The current standard in the U.S. is $0.091 per reproduction. For online streaming, payments can be as low as $0.0022 (for subscribed listeners) and $0.0017 (for unsubscribed listeners). When a popular song is used in a movie, TV show, ad, or video game, its creator(s) can make between $5K and $400K.

Do cover songs need to pay royalties to the original composer?

If you’re covering a song by another artist and performing or releasing it publically, you must pay the song’s original composer a fee. While you’re the owner of the separate work of art that’s the cover song, the song’s original creator(s) is still entitled to the authorship rights.

How do music artists get paid by Spotify?

To get paid by Spotify, music artists need to license their songs with a performance rights organization (PRO). Spotify and other online streaming services will then pay a certain sum (usually under $0.0022) to the PRO every time a song’s streamed. Authors later collect this sum through their PRO.

There’s a caveat to the way Spotify works, though: reportedly, the streaming platform only pays for a stream if the listener spends more than 30 seconds streaming a song. Spotify’s 30-second rule makes for a highly controversial topic.

You can learn more about how Spotify works in this article.

Are music royalties a good investment?

Music royalties are an excellent investment because they work out in the long run. You may have to pay a minor sum to sign up with a performance rights organization (PRO), but you’ll be able to collect royalties on your work for as long as you’re alive.

If your goal is to work as a professional musician, signing up with a PRO is a must. The steady payments you’ll get every time your songs are publicly used are a great incentive, but there are other advantages, including copyright protection.

Summary

The old, romantic idea that art and business don’t match doesn’t cut it anymore. To go from starving artists to professional songwriters, music creators need to make the most of every opportunity they have. Collecting music royalties should be a priority to any established, up-and-coming, and even beginner musician.

If you’re a creative who releases original work—whether it’s music or any other type of art—it’s important to know how to navigate the ins and outs of royalty accounting, understand how copyright percentages get divided and learn about the institutions that regulate copyright fees in your country.